Among all the family recipes Les Pannequets Saint-Louis is truly a unique one, et je pèse mes mots — that is: and I weigh my words — yes: unique, a word I almost never use.

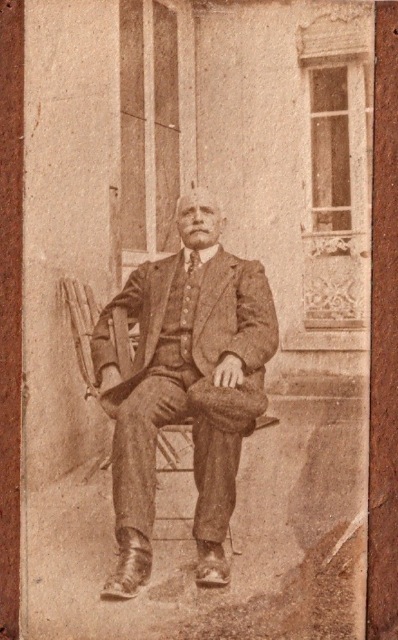

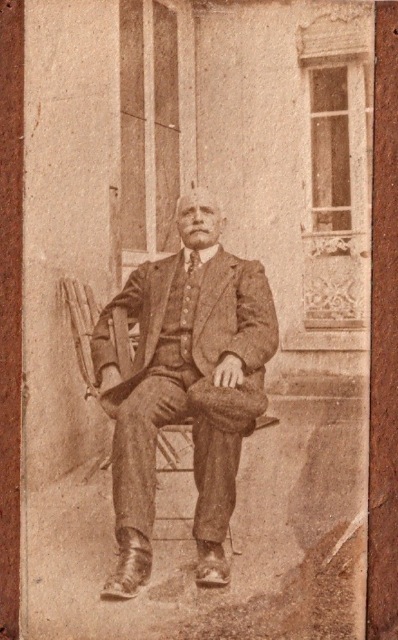

My great grandfather Louis, Gabriel, Marcel, Marie, Peyrafitte (1858-1929) created this amazing recipe that we still make for very special occasions like this Christmas day when Pierre, Joseph, Miles and I gathered around our kitchen island for a true family food communion.

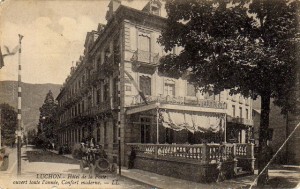

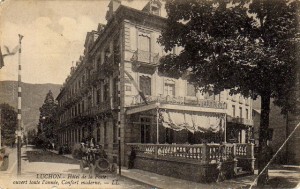

Pannequets have been part of the French cuisine repertoire for a long time, though the word derives from the English “pancake”— from the middle English pan +cake —that’s an easy one. The famous French chef, Auguste Escoffier, has several entries for pannequets in the Entremets section of his reference work Le Guide Culinaire. So does Joseph Favre in the Dictionnaire Universel de la Cuisine, mentioning an interesting version of pannequets au gingembre — with ginger. They both specify that it is a Patisserie Anglaise or English pastry. Not surprising at all, in fact, that my Pyrenean ancestors would be acquainted with English desserts. In the 1900’s the French Pyrenees were “invaded” by English tourists, the family hotel in Luchon even changed its name: the Hotel de la Poste became the Hotel Poste & Golf ! My family had sold some land so a golf course could be built for to the increasing (colonial) British clientele. Surfing the net to look for traces of my grandfather Joseph’s stay in England (he was there as a cook between 1902-08), I was quite astounded to find the following entry in “The Gourmet’s Guide to Europe” by Algernon Bastard (probably published around 1903):

Throughout the mountain resorts of the Pyrenees, such as Luchon–Bagnères de Bigorre, Gavarnie, St-Sauveur; Cauterets–Eaux Bonnes, Eaux Chaudes, Oloron, etc., you can always, as was stated previously, rely upon getting an averagely well-served luncheon or dinner, and nothing more — trout and chicken, although excellent, being inevitable. But there is one splendid and notable exception, viz., the Hôtel de France at Argelès-Gazost, kept by Joseph Peyrafitte, known to his intimates as “Papa.” In his way he is as great an artist as the aforementioned Guichard; the main difference between the methods of the two professors being that the latter’s art is influenced by the traditions of the Parisian school, while the former is more of an impressionist, and does not hesitate to introduce local colour with broad effects, — merely a question of taste after all. For this reason you should not fail to pay a visit to Argelès to make the acquaintance of Monsieur Peyrafitte. Ask him to give you a luncheon such as he supplies to the golf club of which Lord Kilmaine is president, and for dinner (being always mindful of the value of local colour) consult him, over a glass of Quinquina and vermouth, as to some of the dishes mentioned earlier in this article. You won’t regret your visit.

The Joseph Peyrafitte (1849-1908) mentioned above is Louis’ brother and therefore my grand father Joseph Peyrafitte’s (1891-1973) uncle who was named after him. Louis & Joseph had married two sisters, Marie & Anna Secail. Anna moved to the Hôtel de France in Argelès-Gazost and Louis Peyrafitte came to Hotel de la Poste in Luchon. The marriages had been arranged by one of the Peyrafitte’s brothers who was a priest at the Vatican with one of the Secail brothers — also a priest. All this is documented — and left a magnificent family heirloom that I inherited: “the Chandelier” but that story is for another blog-post. Both brothers had been classically trained cooks so one can easily understand how the inspiration for this recipe came about.

Hotel de la Poste in the late 1890’s

My father, Jean Peyrafitte, doesn’t remember his grandfather’s cooking very much — he was 6 years old when his grandfather Louis died in 1929 — but he vividly remembers his father Joseph Peyrafitte (my grandfather and cooking mentor) making the Pannequet Saint-Louis.

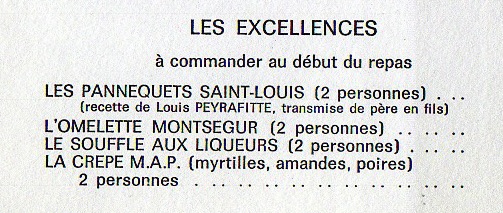

At that time no “grande carte” was available at the restaurant, though there was a menu du jour which changed daily given that the clientele were “pensionnaires” —residents — who would stay for periods of 3 weeks or more. My grandfather would occasionally put the pannequets on the menu but only during low season, as they are incredibly time consuming. The recipe was not written down until the mid 1960’s. At that point my dad decided to promote regional cooking and to upgrade the restaurant to a “grande carte,” hoping to get attention from the Guide Michelin and Parisian food critics. So he created a “grande carte” full of regional dishes like Pistache (mutton & bean stew), Peteram Luchonnais (lamb, veal, and mutton tripe), duck confit, etcetera. My grandfather considered this food low class and believed that lobster and tournedos Rossini was more appropriated.

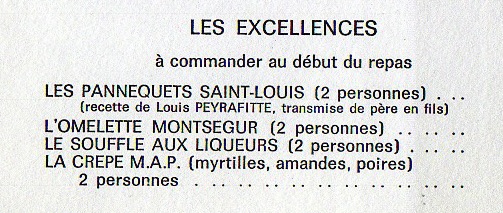

But my father pointed out that the clients could eat that food anywhere, but not our local specialties. That is when the pannequets Saint-Louis made their way to the dessert menu of the grande carte and were listed as “Les Excellences to be ordered at the beginning of the meal (order for 2 minimum)”.

Now this is the part I remember. In the late 60’ my mother begged my grandfather to write the recipe down. He said he couldn’t as he knew it by instinct. She didn’t get discouraged. She stood by him as he was making them, weighed the ingredients one by one and made a note of it. I must say that without my mother (Renée Peyrafitte) most of the family memory would be gone.

When I called my parents to talk about the Pannequet Saint-Louis recipe I reassure them that I wasn’t going to give the recipe away. Mom said, “don’t worry no one else can make them anyway.” What she meant is that this recipe takes total dedication. When my grandfather grew old, it was she who was entrusted with the task of making them. She tried to teach a few cooks but the result was never satisfactory. One of the reasons is that from making the batter to cooking them requires total and utterly focused attention. And if you don’t do that the best dessert in the world turns into the worst glob!

I must say that since a little girl I watched my grandfather & then my mother making them over and over. My favorite post of observation during “service” was in the corridor where I could survey all the action. As soon as I would hear an order for pannequets being “barked,” I would get into position to assist and taste! I have memorized all the gestures. Unlike the regular crêpes the pannequet doesn’t get flipped (but come and see me do that Sunday at the 36th Annual New Year’s Marathon). Once one millimeter of the batter is poured into a hot and generously buttered cast iron pan, it is let to cook until almost, but not completely, dry. Then the edge of the dough next to the handle is gently detached with a spoon and if cooked perfectly the batter will roll down the pan like a cigarette helped only by little tap in the pan. A perfect pannequet Saint-Louis has a very lightly crisp skin on the outside and custard like consistency on the inside. While the texture melts in your mouth, the rum, almond, lemon & vanilla flavors lead you to gastronomic ecstasy! I don’t know if my great grandfather named the pannequet “Saint”-Louis himself, but I doubt it — it sounds more like one of those mischievous puns my grandfather Joseph Peyrafitte was famous for!

Hotel de la Poste became Hotel Poste & Golf around 1905

Happy New Year, Bona Anada, Bonne Année!

And hope to see you Sunday for poetry and crêpes at the Poetry Project for the 36th Annual New Year’s Day Marathon Benefit Reading .

ps: You might enjoy reading these 2 posts about crêpes:

Crêpes History, Recipe + Video:

The Crêpe, the Theorist, the Chef and the Volunteer